HAYES OYSTER COMPANY

Dealers in Shellfish since 1912

About Hayes Oyster Co.

Cold water and low salinity from the five-freshwater salmon-bearing rivers that flow through Tillamook Bay prevent the problems that occur in most of the world's shellfish growing areas.

Tillamook Bay's combination of low salinity, plus two daily tidal infusions from the Pacific Ocean, has created the perfect habitat for oysters, producing the sweetest, fattest, tastiest all-season oyster found anywhere in the world, and arguably The Tastiest Morsels on Earth.

This 1928 Oregon Historical Society photograph, is Jesse Hayes (1883-1957), showing, after planting the first oysters in Oregon, that oysters would not only grow in Tillamook Bay, they would thrive. Cape Meares is in the background.

In 1928, before Japanese oyster seed was introduced to the west coast, the only oyster that existed on the west coast was the small, native, Olympia oyster.

In 1849, the California gold-rush created a demand for the native Olympia's. Large shipments were shipped to San Francisco where that market quickly became a bottomless pit.

That bottomless pit led to over harvesting.

Over harvesting resulted in the Olympia Oysters near extinction, because then, unlike now, there were no oyster farmers, only oyster harvesters.

Since then, in Tillamook Bay, Hayes Oyster Company planted, cultivated, harvested and processed up to 100,000 gallons of oysters a year. They were sold to Safeway Oregon, California and Arizona in 10 oz., 12oz. and 16oz. jars.

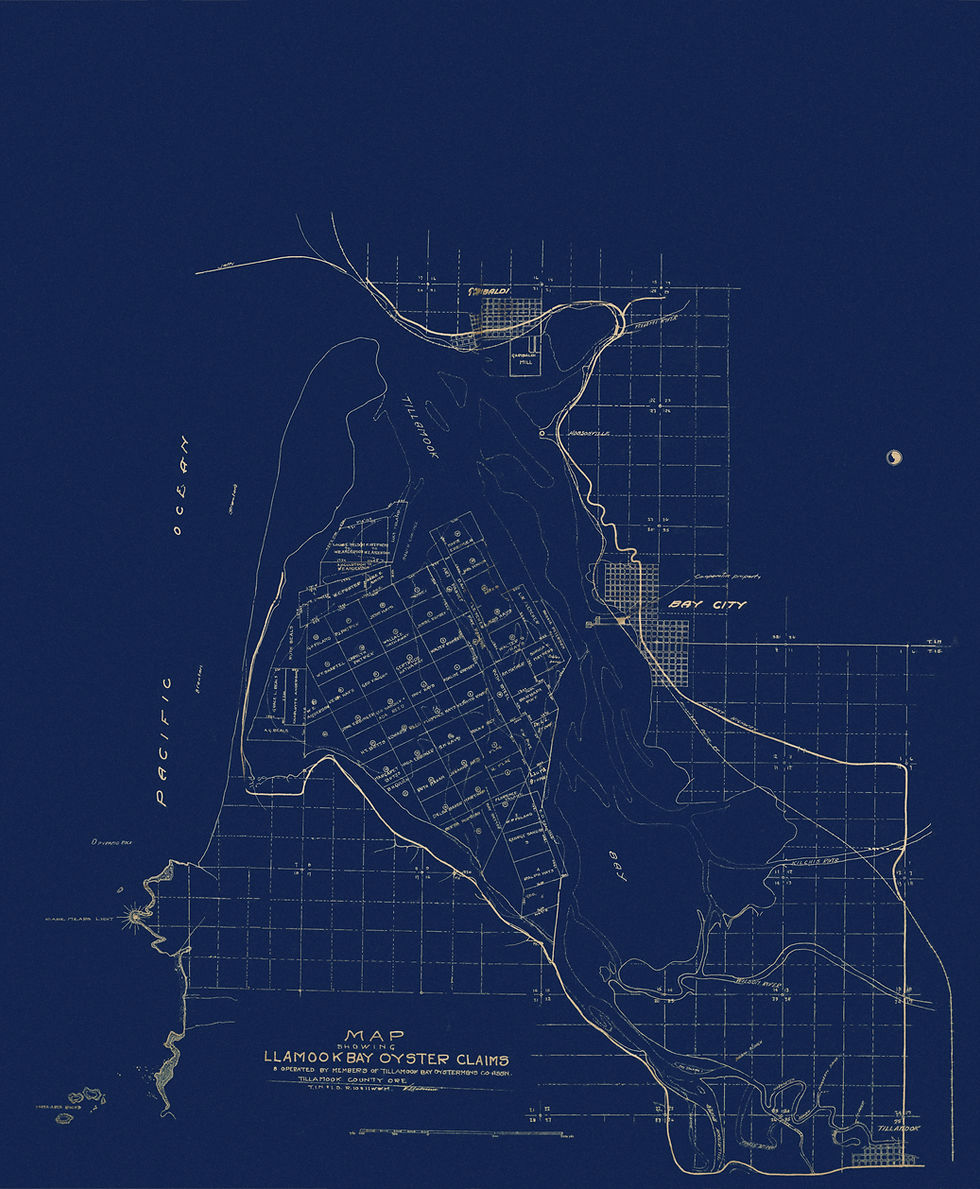

THIS 1931 OYSTER CLAIMS SURVEY MAP SHOWS THE ORIGINAL, GRANDFATHERED, OYSTER CLAIMS ON TILLAMOOK BAY.

IT ALSO SHOWS THE TWO SALMON CANNERY BLOCKS ON HAYES OYSTER DRIVE.

Learning in 1928 that Japanese oyster seed was available in Canada and may thrive in Pacific NW estuaries, Jesse Hayes, from Tillamook Bay, after showing the Japanese oyster would thrive in Tillamook Bay, lobbied the Oregon legislature to pass the "Oregon Oyster Act".

In 1931, "The Oregon Oyster Act" was passed, giving citizens the right to lease State lands, under water, for the purpose of growing oysters. To lease state land for oyster farming required an official survey of Oregon's oyster growing grounds. These original leases are referred to as "Legacy" or "Grandfathered Oyster Claims".

The original map, shown below is the "1931 Survey of Oyster Claims for Tillamook Bay". The map also shows that Tillamook Bay's oyster claims were platted into 50-acre parcels because at that time, the Act read: "One fifty acre claim per person".

The name written in each Plat is the name of the original lease holder. Nearly all were relatives or friends from Bay City, Garibaldi and Tillamook. We soon changed the law, eliminating the one Plat per person restriction. The original lease holders soon became discouraged and gave up. Jesse Hayes bought most of those leases and Hayes Oyster Company was born.

The two Bay City salmon cannery properties (Parcel 1. and 2.) can be seen on this map. On the lower left, you can see the Cape Meares Lighthouse.

The 1982 photo below shows Sam, Verne and Lynn Hayes, still oystering 50 years after the 1932 photo above. The 1982 photo was taken on the dock in Bay City.

The photo shows the Oyster Cooperative Property in Bay City, with Jesse Hayes on the dock. Three of his six sons, Sam, Verne and Lynn, are on barges loaded with oyster seed from Japan. On the high tide, they will be towed to the beds for planting.

Planting seed meant scattering the seed high in the air with forks or shovels so the shells, covered with babies, would be spaced evenly as they sank to the beds. Spacing was important because one shell with babies attached may become a two foot wide cluster of a dozen or more oysters.

Before the seed was shipped from Japan, the wood for the boxes was submerged in mud flats to soak for months, allowing the seed to stay cool and damp for the two plus weeks long trip from Japan to their beds in Tillamook Bay.

On the right, you can see the discarded boxes. The Japanese used this same method for shipping seed for the next sixty years.

The Cooperative Property is also shown on the east end of the above 1931 Oyster Claims Survey Map.

DEALERS IN SHELLFISH SINCE 1912

In 1910, the Oregon Fish Commission began issuing Shellfish Permits. In 1912, Jesse Hayes applied for and received the first Shellfish Permit for Tillamook Bay.

The article below, from the March 17, 1922, Bay City Examiner, records his and his then partner's shipment of salmon to San Francisco, where he also wholesaled crab, clams - all out of Tillamook Bay.

For many years in the early fall, the USAF Survival Training Mission brought their Instructor Training Branch to the Tillamook Bay spit for a two-week survival course. The instructor trainees were dropped into the bay from helicopters, they had no food or water and had to learn to survive with what was there, even learning how to dig and construct wells for water - in sand. Every year, Sam allowed them onto Hayes Oyster Company’s oyster beds as part of their survival training. At the end of each mission, they invited us out for a celebratory last meal. The staff and trainees always had a lot of questions. Most had never eaten or liked oysters, crabs or clams, but after the course, they had a change of mind.

To Mr. Sam M. Hayes

"In Appreciation For The Many Years Of Valuable Assistance Provided To The 3636 CCTW (ATC) Instructor Training Branch In The Accomplishment Of USAF Survival Training Mission"

In October 1989, Sam Hayes, President of Hayes Oyster Co., was named to the DIAMOND PIONEER ACHIEVEMENT REGISTRY of the OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES.

In 1989, Sam successfully worked with the Oregon legislature to transfer Oregon's oyster industry from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife to the Oregon Department of Agriculture. Seeing his success, the Washington State oyster growers asked him to help them do the same in Washington, and he did.

During WWII, Japanese seed was not available. Sam found a large bed of oysters – a natural oyster set in the Nemah Sink, near South Bend, Washington. He drove both our dredges from Tillamook Bay to South Bend in Willapa Bay where we founded Coast Oyster Co. That find was large enough to carry us through the end of the War.

After the War, when Japanese seed became available, Jesse Hayes and Sam Hayes returned to Tillamook Bay. Verne remained in South Bend with Coast Oyster Company. We all began planting a lot of Japanese seed. Sam brought one of the dredges back to Tillamook, the other stayed with Coast in South Bend.

The article below is from the October 25, 1989 issue of the Tillamook Headlight Herald.

BEFORE OYSTER HATCHERIES:

Oysters spawn (reproduce) in the warmest water of the year. The spawn can turn the water milky white. That milky water is billions of baby oysters.

Baby oysters are able to swim for about a month. Within a month they develop a sticky tail, their shells begin to harden, and they sink, and set. The babies will set on anything smooth - preferably old, clean, oyster shells.

When the time comes for them to sink and there is nothing for them to set on, they die.

When the babies set, it is permanent, and once set, they will be left in place to winter-over, hardening up before the trip home to Tillamook Bay in the early spring.

It will be another year and a half to two years before they are ready to harvest.

Before oyster hatcheries, NW coast oyster farmers had two options for seed. One was catching a natural set, the other was importing seed from Japan. For many years, Hayes Oyster Co. did both.

We caught our seed on a mile of beachfront on Dabob Bay, Washington.

Dabob was a well-known estuary for catching natural oyster sets because in the summer it had little circulation and the water temperature would get warm enough for a spawn, and, for the spawn to live long enough and not be moved out of the setting area.

Tillamook Bay does not allow for this kind of operation because its cold water would not allow oysters to spawn and if there was a spawn, the cold water may kill it. Also, Tillamook's two daily tidal changes would move, doom, any spawn away from the setting area.

In Bay City, for the purpose of catching these baby oysters, holes were punched in seasoned shell and strung onto 10' wire strings. Twenty-five wire strings were tied into bales for transporting them to Dabob Bay.

Depending on a natural set was an uncertain way to rely on seed because during the month the babies were swimming, a cold spell, rain or wind on Dabob may kill or move the babies out of the setting area. The result may be a years seed supply lost. We had years when there was no set, or a small set, or a good set, or, a very good set.

We were always at the mercy of mother nature.

This August 1973 photo shows Sam Hayes, President of Hayes Oyster Co., on the beach at Dabob Bay, inspecting that year's set. In Bay City we punched holes in old oyster shell and strung them on 10-foot wire strings for transporting to Dabob.

In 1978, at a time when Pacific west coast oyster farmers were dependent on Japanese oyster seed, the Amoco Cadiz oil tanker broke in half and spilled 1.6 million barrels of crude oil into the English Channel near the coast of France. Rough seas and a strong NW wind blew the oil onto the French coast.

Amoco Cadiz oil spill - Wikipedia

That tragic accident decimated France’s entire oyster crop. The result of that loss was:

The French made a deal with the Japanese seed suppliers and sold the NW coast oyster growers annual seed supply to the French growers.

The NW Oyster Industry lost that year's seed supply. Angered and vowing to not let it happen again, it turned out to be a good thing because it fired-up the Pacific NW oyster growers.

Spearheaded by Verne Hayes, with aid from federal and state Sea Grant funds, and the University of Washington scientists under Prof. Kenneth Chew, NW growers did successfully develop the Oyster Hatchery.

Verne, aways looking for ways to improve the oyster business, and fascinated with technology, studied the progress of oyster gametes in water from the bay. With a microscope, he could see that when the larvae had developed the signature D shape, they were ready to set, he would then quickly put them on strings of clean oyster shells on the beds trying for a set.

He religiously tested water temperatures, hoping for the 21 days of little wind and warm temperatures that would make it possible for a successful set.

It was an uncertain procedure and led him to think about better ways of ensuring an annual crop of oysters. He successfully tried getting a set by taking fertile male and female oysters, liquefying them so he could, at the critical time, put them on blank shells on the oyster beds. Life Magazine sent a reporter and a photographer out to capture that innovation.

The Hatchery could now grow single oyster seed. Each oyster seed was attached to a very small single grain of shell. When the oysters were large enough, they would be taken from the hatchery and placed on the beds until they were harvested.

Another of Verne's lasting and important contribution to the Oyster Industry was his work with the Marine Biology Department at the University of Washington to develop and scale up the development of a Triploid oyster. Triploids would be grown at the Coast Oyster Hatchery at Quilcene - which he developed and financed.

The Triploid oyster, like a steer, is infertile and grows all year without spawning or expending energy in reproduction.

The age-old problem of the oyster farmers' crop uncertainty was solved. The result was a more uniform and faster growing oyster. The Hatchery stands today as a cornerstone of modern oyster farming and revolutionized the industry.

Verne Hayes deserves to be remembered for his groundbreaking work.

The Plaque below, given to Hayes Oyster Company, after Verne's death, is in gratitude for his successful industry wide innovations.

This photo taken at Coast's Quilcene hatchery, shows 50 bags of newly set seed ready to be trucked to Tillamook Bay for planting.

The seed was caught on old shells that were strung on ropes and put into bags for the purpose of setting into the hatchery tanks.

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

OYSTER HATCHERIES REVOLUTIONIZE THE INDUSTRY

September 13, 1986, By Ken Slocum, Staff Reporter

Suddenly The Oyster Outlook Is Bright In the Pacific Northwest.

Big things are happening to oysters in the Pacific Northwest.

An industry that was stuck in the mud not long ago has been resurrected,

the result of breakthroughs in mass-producing oyster larvae.

If this sounds ho-hum, you're not an oyster grower - or oyster eater.

"It will revolutionize the industry; it's the biggest thing to happen in the history of the oyster," says Verne Hayes of the breakthrough developed in the last couple of years at the University of Washington.

Mr. Hayes is president of Hilton Seafood's Co., the parent of Coast Oyster Co., the giant among some 100 West Coast growers. What's giving the Northwest oyster industry new momentum was the discovery that oysters, like fish, can be bred in hatcheries and then put into local waters to grow and mature.

Until the Pacific Northwest developed oyster hatcheries in the late 70's, most West Coast oysters could be stamped "Made in Japan", because, oyster seed was shipped, from Japan, in crates, then deposited in West Coast oyster beds to mature. The process was unpredictable and expensive.

The hatchery system has turned the industry on its head.

Last year (1985), Coast Oyster produced 16.5 billion larvae - about 70% of West Coast hatchery output. These days, about 80% of West Coast oyster production comes from hatchery-raised larvae.

Today, hatchery seed makes planting easier. This photo shows 125,000, 3mm, baby oysters ready to plant.

"The oyster seed I ship in a little Styrofoam cooler will eventually fill several dump trucks," says Lee Hanson, owner of Whiskey Creek Oyster Farm, one of the Northwest's oyster hatcheries.

Before single oyster seed, we planted seed in bags that held 50' ropes. Each rope was spliced with old, clean mother shell. The bags were then placed in hatchery tanks where the babies would set for life.

After bringing them to Tillamook, we placed the bags on pallets on our beds, to overwinter. In the spring we took the ropes out of the bags and spread them on the beds where they stayed until they were ready to harvest.

Garibaldi can be seen across the bay.

This seed has been out of the hatchery for seven months. When it came from the hatchery, it was the size of something out of a pepper shaker.

This 1949 photo Hayes Oyster Cannery and notes: "Capacity - 500 cases canned oyster stew per day."

You can see the boiler above the truck cab

Before WWII, the American public ate little seafood. During WWII, meat became scarce and was strictly rationed.

That rationing resulted in a new public awareness and demand for fresh seafood (fish, crab, clams and oysters).

Before WWII, because of the short shelf-life and little local demand, Hayes Oyster Company canned oyster stew.

During WWII, the U.S. Military consumed a lot of canned oyster stew.

After the War and by the early 1950's, because of the new market for fresh seafood, we stopped canning oysters and began wholesaling oysters fresh, in glass jars.

Today, we see another change in the oyster market from canned, to fresh in jars, and now, fresh in the shell.

Many people prefer oysters in the shell because during the process of shucking, washing and packing, the oyster loses its liquor, whereas, oysters eaten fresh out of the shell retain that liquor - in their cupped shell.

The photo below shows the label we used during the years we canned oyster stew. At home, we had cases of stew from which we enjoyed plenty.

The Chinook Observer

NW OYSTER HISTORY

RUGGED INDIVIDUALS

By DOUG ALLEN

OCTOBER 1, 2003

LEADERS OF THE NW OYSTER INDUSTRY OF THE PAST 70 YEARS,

PART 1

The oystermen of the 20th century were, at the very least, a highly competitive lot. With apologies offered, the list is long, and not all of the stories will be told.

JOE DOUPE' - Ilwaco Oyster Co.

Joseph H. Doupe was born in County Limerick, Ireland in June, 1881, the seventh of 10 children. After keeping books for department stores in Ireland for six years, young Doupe and two brothers joined an older brother in Portland, Oregon in 1904.

In the next few years the young Irishman established himself in a new home and met his bride-to-be, Margaret Rogers. The couple wed in 1909. Margaret had been born in Minneapolis in 1887 and come west with her parents. Her father, Charles Fremont Rogers, owned and operated the Ilwaco sawmill.

When Japanese oysters were first planted in the late 1920s, Joe and Harry decided to try their hand in the oystering business. The Ilwaco Oyster Company was organized in 1930, with the original investors, including the Doupes, Clyde Woodham, Ira Murakami, Roy Herrold, John O'Meara, Bub Baker, and brothers Alex and Bert Shier. With $35,000 raised from the initial investment period, the company purchased oyster land, built and acquired boats, and constructed the small plant which was later expanded and known as the Jolly Roger.

Under the direction of Doupe, for the duration of its existence, the company's oysters were largely shipped to California markets. Not all of the original investors stayed with the company: During the first year Ira Murakami chose to withdraw in order to start his own oyster business.

In August 1951 Doupe accepted an offer to sell the company to Verne Hayes for a half of a million dollars. When the transaction was completed, company properties were transferred to Coast Oyster Company, "lock, stock, and barrel." At the time the deal was believed to be the largest and most important sale in the history of the Willapa Bay oyster industry.

The Ilwaco Oyster Company was an important contributor to Willapa Bay's total oyster industry. Several of the company's initial stockholders and more than a few of the key employees went on to play significant roles with other companies, including Ira Murakami, Harland Herrold, Wallace Woodham, and others.

VERNE HAYES - Coast Oyster Co.

You've heard the story of the man who bought the Brooklyn Bridge? Verne Hayes could have been the person who sold it to him. Those who knew the man admired his ability to talk and attract prospective investors. The adjective convoluted might best describe his actions and personality. Associated words include entangled, multilayered, twisted, and devious. "Verne Hayes was a good guy - he created a lot of employment for a lot of people around here.

"Ownership and Management:

In November 1946, Hayes purchased 51 percent of Arnold Waring's Haines Oyster Company. The transfer of stock gave Coast Oyster Company control of all of the Haines company's oyster ground, oysters, equipment (including boats and dredges) and leases. Coast also took control of 1,000 acres of oyster ground at Netarts and 2,500 acres at Tillamook Bay.

Throughout the '40s several oyster businesses were acquired by Hayes, including Johnson-McGowan, Long Island Oyster Company, Eberhardt Oyster Company, Eagle Oyster Packing Company, and and the Ilwaco Oyster Company. With these transactions Coast gained control of the former Willapoint and Bay Point oyster grounds. During this time Verne held the company position of vice-president and general manager. Company attorney Ward Kumm, Seattle, was president, with George Clark the secretary-treasurer.

Using the Willapoint brand, and with the addition of Ilwaco Oyster, Coast's holdings had become the largest in the Pacific Northwest. Hayes' contrived claim of 350,000 gallons of oysters harvested and sold per year was unrealistic, as it amounted to more than one-third of the output of all the companies in the Northwest. (Although the claim was exaggerated, by 1951 Coast had grown quite large, with plants at South Bend, Bay Center, Nahcotta, Poulsbo, Allyn, Eureka (California), Oregon, and at Grass Creek on the north shore of Grays Harbor. )

In 1950 a Tillamook schoolteacher dropped by the South Bend plant to say hello to his former seventh grade student. Although Hayes was not at the plant, the teacher told his hosts that as a seventh grader Verne had dreamed of being the world's biggest oyster farmer. Ed Gruble remembers that Hayes, still dreaming the dream, confided that his goal was to produce one million gallons of oysters a year. Today, veteran oystermen smile and wag their heads when they hear these numbers.

In the early 1950s Hayes convinced Van Camps Seafood to take over the sales of the company's oyster stew operation. (During the time Van Camps owned the company Coast sold oysters under the "Chicken of the Sea" label.)

In 1948 Hayes met Ed Gruble at a mutual friend's Seattle home. Gruble was soon convinced that he and his two trucks (used to haul produce on a seasonal basis) would be a good fit during the winter's oyster packing season at South Bend. Soon after arriving in South Bend, Hayes asked the inexperienced Gruble to assume management of the troubled plant. A quick learner, Ed soon had doubled the cannery's output and had worked himself into a fulltime position.

As Gruble tells the story, unfulfilled promises convinced him to quit the company in late 1951. Within months he had started his own oyster stew business, known at that time as the Willapa Bay Oyster Company. In 1954 Ed and two new partners renamed the business the Hilton Oyster Company and moved it to Seattle.

Bringing in the Big Players In early December 1955, Hayes announced that both B. C. Packers, Ltd. and Chicken of the Sea, Inc. (Van Camps) had purchased an equal amount of Coast Oyster common stock. With the changes in the company, B. C. Packers assumed the sales of the fresh and frozen seafood, while Chicken of the Sea continued as they had - as the company's exclusive sales agent for canned oysters and canned oyster stew. (Located at Steveston, British Columbia, B. C. Packers was, at the time, the largest salmon packer in the world.)

Regardless of the seemingly positive changes in the operation, the company lost money. Van Camp soon wanted out, and B. C. Packers assumed a larger role in the company. (Most likely because the Canadian company wished to protect their investment.)

Stan Sheriff (of B. C. Packers) was assigned to be Coast's West Coast sales manager. Shortly after Sheriff had taken over the head office, B. C. Packers grew uneasy with Verne Hayes and arranged to have attorney Ward Kumm to take control of the company. With Sheriff and Kumm at the helm by the end of 1955, Hayes was ousted from any position of authority with the company.

Fiasco at Eureka: Hayes headed for Eureka and Humboldt Bay where the unflappable promoter found another investor to put up money for a new operation - raising oysters on wooden racks. The operation was a disaster - the wood used for the racks rotted, and when Verne tried treated wood the sets failed. Wallace Woodham remembers, "Verne spent $150,000 to get the plant ready in Eureka, then the oysters turned black.

"Without oysters there was no business, and facing imminent losses, the investor wanted out. The undaunted Hayes found another skittish backer, but the new man was soon scared off.

In a surprising twist to the story, Coast Oyster came to the rescue of the Humboldt operation. New money was infused into the venture and in October, 1956 Ralph Hayes (one of Vern's five brothers) smashed a bottle of champagne over the bow of a newly constructed hydraulic dredge named in his honor. In attendance at the celebration were Eureka city officials, the designer of the dredge, R. H. Bailey, along with the Dr. Roy Elsey, aquaculturist and vice-president of B. C. Packers.

Designed along the lines of an Alaskan gold mining dredge, the "harvester" never performed as expected. Wallace Woodham remembers that to took $90,000 to refit the dredge after the first year. "Originally designed to be towed, it was supposed to dredge in a circle. It's still used, though, on this bay.

"More Changes: Wayne Morris first arrived at South Bend in 1958, having managed the Allyn plant from 1956. (Wayne had earlier worked for Coast in 1955, at Eureka.) After Morris first supervised the plant operation, Richard Murakami asked to 'borrow" Wayne for the beds operation while the cannery was closed during the winter of 1958-59.

As Wayne explains, "After that I ran the oyster grounds under the supervision of Richard." Wayne also recalled that at the time the South Bend plant was daily producing 2,000 cases of oyster stew.

Hayes' troubles returned in the early 1960s. B. C. Packers wanted him out, this time for good. Coast bookkeeper Dory Haldorson, officially under the employment of the Packing company, was named as Coast's new general manager.

It was a time of much intrigue. Hayes had been accused of arranging sales of various plants (canneries) while hiding his intentions of recapturing majority control of the stock. An example of this concerned the Coast plant at Poulsbo. Joe Engman had purchased the plant, but discovered Hayes' scheme. Engman's payment was directed to creditors, stifling an effort by Hayes to persuade other shareholders to join his "movement." (Engman's plant became known as the Keystone Oyster Company.)

Dory Haldorson remained at the helm of the company throughout the balance of the 1960s and 1970s. To Haldorson's credit, Coast remained active and maintained its position as one of the largest oyster operations in the region. During this time canning operations were halted and all oysters were shipped to the South Bend plant to be processed fresh or frozen. Richard Murakami and Wayne Morris continued to work as Coast's Willapa Bay supervisors.

At Nahcotta Wallace Woodham ran the oyster grounds operation. Jeff Murakmai still worked everyday, but age had slowed down the veteran oysterman.

For all practical purposes, Wayne Morris was the man who ran the Coast operation during these years. Today, Tim Morris, Wayne's son, oversees the company's oystering and Manila clam business.JOHN PETRIE: In 1982 John Petrie led a group that purchased Coast Oyster Company. Petrie's partners were Floyd Bagley and none other than Verne Hayes. Although Verne had amazingly re-emerged as an owner, times had changed. It was during these years that a catastrophic fire destroyed the South Bend plant. Revamped insurance coverage paid for a new plant which Hayes helped design. Verne passed away in 1989.

The changes were not done. Clear Springs Trout Company of Idaho acquired Coast late in the decade, but then grew troubled with the financial situation of the company. (Clear Springs is more than a fish farm company; several investors are millionaire owners of the Ore-Ida potato fortune.)

By 1992, Clear Springs decided to cut its losses and turned the business over to the mortgage lender. It has been suggested that the company lost as much as $8 million in its turn as owner of Coast.

With the bank holding a huge financial burden, John Petrie managed to re-acquire Coast for only a portion of the debt. (The total debt was reportedly in the neighborhood of $12 million.) Since that time Petrie has had complete control of the company.

Regardless of who owns today's Coast Seafoods, the name Verne Hayes still resonates among the oystering community. The name Verne Hayes can still cause blood to boil and talk to become heated.

MALCOM EDWARDS: Oysterman and PCOGA official.Malcolm B. Edwards had a succinct description of his oystermen comrades, both friend and foe. Tongue in cheek, he called them "rugged individuals."

Like many of his generation, Edwards was essentially a self-educated man. He quit school in the eighth grade to help support his parents, who ran a small nursery business on Eklund Park hill (South Bend). Eventually, Edwards became a land surveyor through correspondence courses and practical work at the Pacific County engineering office.

Edwards acquired his first oyster ground during the Depression, a small parcel at Stony Point. After serving in a U. S. Navy construction battalion (CBs) in the South Pacific during World War II, he returned home to establish an independent engineering office, as well as build a small oyster business.

Malcolm served several years as the director of the Pacific Coast Oyster Growers' Association.

"Dad worked with Verne Hayes of Coast Oyster to capitalize on the oyster's 'apocryphal aphrodisiac' with virility powers. They developed a pill using dried oysters with vitamins and minerals added. I believe the pill was manufactured in Japan. The effort went so far as to get government approval, which was the same color as an oyster, under the brilliantly conceived name 'Retsyo,' which, of course, is oyster spelled backwards. The pill failed in the market as well as in bed. I think this episode was in the late '40s or early '50s."

When Coast Oyster Company decided to build an oyster plant in Japan, Hayes hired Edwards and sent him to Japan to help design and implement U. S. sanitary and automation standards.

" I don't know what ultimately became of the cannery - my guess is that it was sold to a Japanese buyer. Dad was also responsible for negotiating seed contracts from the Japanese and then making sure it arrived safely in the U. S. It was a mammoth undertaking with thousands of cases of seed arriving at the Port of Willapa Harbor for distribution." (Hayes Oyster Co.'s seed also came through Willapa Harbor.)

The company Verne created to develop, package and promote his oyster pill sold for a profit.

In Bay City, because of Verne's pill, Hayes Oyster Company installed a large walk-in quick freezer. We graded and separated oysters into male and female, then quick-froze them in five-gallon pales. A lab converted them into pills. They were packaged in beautiful gold boxes. The pills were packaged in pairs - one blue for male, one pink for female - one in the morning, one at night. Many were sold in Japan. In the USA they were called OystaMins. I believe they were once advertised in Playboy for their "Vim, Vigor, and Vitality."

This photo, taken in the early 1950's, on a Coast Oyster Co. bed in Willapa, shows Jesse Hayes (with hat, tie and oyster knife) helping University of Washington and Washington Department of Agriculture representatives better understand oyster farming.

HOW THE GENETIC INTEGRITY OF THE KUMAMOTO WAS SAVED

In the early 1990's, with the advent of oyster hatcheries, the hatcheries began experimenting, cross breeding Pacific oysters with Kumamoto oysters.

NW oyster growers soon realized they may be losing the pure genetic strain of the Kumamoto.

Soon, no one could tell what was or what was not a pure Kumamoto. The industry even named the new crossbreed, calling it a Giga-Moto.

Growers and news reports told us there were, supposedly, no Kumamoto's left in their native Japan, at least not enough to allow exporting Kumamoto seed to NW growers.

Hayes Oyster Company had been raising Kumamoto's since the Japanese seed first became available in 1948.

Anja Robinson, from Oregon's Hatfield Marine Science Center and a longtime friend of Hayes Oyster Company's, asked us if we could find her a genetically pure Kumamoto. We did, because all our Kumamoto seed came from Japan.

We had an old, abandoned Kumamoto bed and were able to find about a bushel of twenty plus year old Kumamoto’s. They were beautiful and as big as a grapefruit and were pure Kumamoto stock.

We drove them to Anja and Willie Breeze at the Hatfield Marine Science Center. It was their due diligence that gave us the genetically pure Kumamoto we have today.

It was Anja Robinsons passion that spearheaded and played the vital role in giving the world pure Kumamoto genes. As a result, the world is a happier place.

Anja received little credit, due to the fact, it was said, she didn't have a Doctorate degree, so -

Thank You, Anja

This is a Hayes Oyster Company twenty-plus year-old Kamamoto from the bushel donated to the OSU Seagrant Lab in Newport - for the purpose of preserving the integrity of the Kumamoto gene.

This Kumamoto is just under six inches long.

In April 2011, OPB/PBS produced a history of Oregon's oyster industry titled: "THE OYSTERMEN".This OPB documentary shows until 1928, when Jesse Hayes planted the first oysters in Oregon, there were no oysters farmers, only oyster harvesters. Harvesters brought the native Olympias to near extinction.

https://www.pbs.org/video/oregon-experience-the-oystermen

Looking south, this Aerial Photo shows the lowest tide of the year on Tillamook Bay. It is a minus 1' 4" tide.

Garibaldi is in the foreground.

Hayes Oyster Drive in Bay City, is about nine o'clock.

Cape Meares separates Tillamook Bay from the Pacific Ocean.

The Bay's only entrance to the Pacific is through the bar, shown on the lower right corner.

Netarts Bay and Cape Lookout can be seen south of Tillamook Bay.

After decades of creating hundreds of local jobs, Bay City honored Hayes Oyster Company by renaming "C" Street to - HAYES OYSTER DRIVE.

This photo shows the East end of Hayes Oyster Drive. Following the street West, it crosses Hwy. 101, and into Tillamook Bay, where for over a century the two salmon canneries operated.

Bay City's Methodist church in the background is the oldest standing church in Tillamook County (1893).

On the lower left, a bit of Cape Meares is seen across the bay.

FOR SALE TWO HISTORIC SALMON CANNERY WATERFRONT PROPERTIES

EACH PROPERTY IS A CITY BLOCK OFF OF HIGHWAY 101,

IN BAY CITY, OREGON

The aerial photo below shows the two salmon cannery properties for sale on the western end of the Bay City pier (Hayes Oyster Drive). Only stub piling remain.

These two cities blocks on the pier have no comparables, and are the only private properties on the pier.

Both parcels are Shore-Land 2 Zoning, and located on a filled pier that runs west into Tillamook Bay.

Both properties were salmon canneries from the 1800's until the late 1950's.

Each property can be developed into a destination resort, seafood facility, or a commercial project.

When Pacific Seafood widened and improved Hayes Oyster Drive in 1991, that development required a public boardwalk and parking on the south side. All new development will require piling and the same street improvements. The street's surface, water, sewer and the boardwalks were extended to the east end of Parcel 1.

Pacific Seafood's improved leased property abuts Parcel 1. Their property is leased from the Port of Garibaldi.

Bay City is the only location, the only town, where Highway 101 meets Tillamook Bay, and is the nearest location on the Oregon Coast to the Portland/Vancouver metropolitan area.

From the Portland metropolitan area, Bay City is a beautiful 90-minute drive over the Coast Mountain range and through the Tillamook State Forest.

On Highway 101, in Bay City, at a yellow blinking light, is the intersection of Hayes Oyster Drive, and Highway 101.

Turning west at the blinking light puts you on Hayes Oyster Drive west. Turning east, at the blinking light, you enter the town of Bay City.

PARCEL 1, on the north side of the Bay City boat basin is 260' along Hayes Oyster Drive and runs 100' into the boat basin.

PARCEL 2, at the west end of the pier, is a 200' x 200' City block.

Bay City vacated these streets, giving both properties an extra 16' on all four sides.

All the salmon cannery structures are gone, and only reclaimable stub piling remain.

Both properties have 360-degree views of Tillamook Bay, Bay City, Garibaldi, Cape Meares, and the Tillamook Coast Mountain range, plus views of the moon and sun rises and sunsets.

These properties enjoy some of the cleanest air and water in the world in one of the safest counties anywhere.

With a few employees and a small space, one could easily raise millions of dozens of single oysters year after year.

In this 1960's aerial photo, you can see stub piling on the south side where the gillnetter's hauled out their nets for repair on a large wooden platform.